In September 2003 I visited the friendly city of Arhus in Denmark to deliver a talk at the JAOO conference. At that time, JAOO was an established software development conference, with well-known speakers such as Martin Fowler, Kent Beck, Linda Rising, and Erich Gamma. And me.

When I arrived at the venue, one of the organizers offered to give me a guided tour of the building. While we strolled through the conference center, she enthusiastically pointed out the major rooms where the conference would take place. Then all of a sudden, the organizer stopped at a wooden door in a small hallway. She opened the door respectfully and we looked in. An ill-lit room with furniture stacked to the walls. “Do you know what happened in this room?” she asked me almost whisperingly. I shook my head. Of course, I had no idea. She continued mysteriously. “This is where during JAOO last year, Kent Beck and Erich Gamma conceived JUnit.”

I guess that was my first introduction to unit testing.

The impact of JUnit on the industry of software development was huge. It was the first viable unit testing framework out there. Still, unit testing took a long time to gain traction. Even today in 2020, when I ask audiences at talks for a show of hands about who actually writes unit tests, most people do not raise their hands. And that’s a shame really.

Recently, I was coaching a development team that had come to a complete standstill. They didn’t dare to change another line of code, afraid the codebase would break. Not a single feature had been delivered to their clients in over ten months. When we investigated their codebase, we found few unit tests, extremely low code coverage, high cyclomatic complexity and many untested paths in the code. And still, when I stressed the importance of solid unit testing for maintaining quality and speed of development, the developers stared at me with long faces and asked if writing all these tests was really, really necessary.

It is.

To be totally honest, it took me quite some time to get convinced of the effects and benefits of unit testing and test-driven development. For authors Kent Beck and Erich Gamma, the number one goal for creating JUnit was “to write a framework within which we have some glimmer of hope that developers will actually write tests.” They built JUnit with already existing, familiar tools so that there was little new to learn. As they said: “It has to require no more work than absolutely necessary to write a new test.” Gamma and Beck made writing unit tests as simple as possible.

So why is it so hard to start writing unit tests?

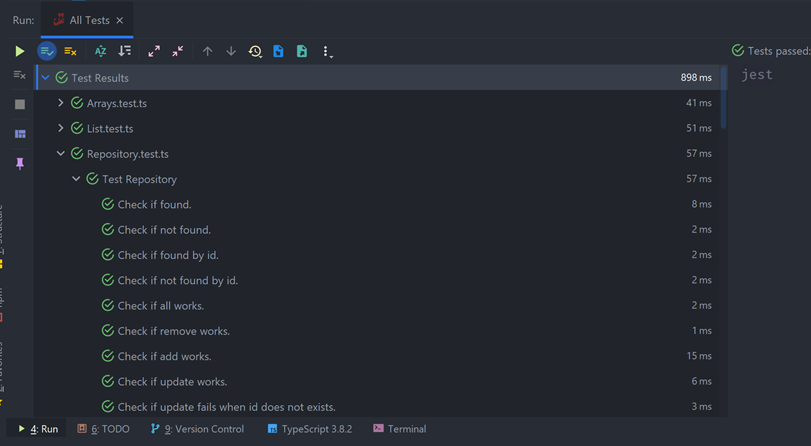

From my own experience, despite the simplicity of the tooling, with Jest being my current poison to test my TypeScript and JavaScript code, one problem I think lies in the fact that writing unit tests still requires skills and understanding. It takes time to learn. And time is something we are always short of in software development. There is continuous pressure from stakeholders, managers or product owners to add and improve features in our products. We never seem to have time available to work on the quality of our architecture and code. Hence, we tend to skip writing unit tests.

Another challenge is that the benefits of having good unit tests are reaped in the long run. People are not really good at preparing for long term benefits. Not unit testing is like smoking. We all know smoking is bad for us. Nonetheless, people find it extremely hard to stop smoking. This is because the drawbacks of smoking are usually not felt until years later. With unit testing, this is quite similar. Having unit tests for everything pays back in the long run. It pays back after six months when you notice you can change your code without pain. And it pays back after one year when you can still change the code. And even after multiple years, your code remains stable and has even become more robust than it ever was. Unfortunately, too many people postpone writing unit tests until its late, and the consequences of not having tested code have become huge.

And it becomes worse when you work with modern software architectures, such as microservices or serverless, where you usually do not have a single codebase, but rather work on a vast collection of small codebases. With one of my recent clients, the total landscape consisted of around forty micro-applications, fifty microservices, and about the same number of serverless functions, each of which with their own codebases, pipelines, and infrastructure. In environments like these, it becomes even more vital to keep your codebases in good health. Unit testing is essential.

As an example, while writing this post, my teams and I are looking at a small, but a rather delicate change in the core library of my client’s landscape. This library contains around fifteen hundred lines of code. Around thirty applications and microservices running in production depend on it. Without even giving it a second thought, we made the change; we ran the three-hundred-eighty-five unit tests on the library; saw that these all turned green; we checked in the code. No pipelines broke in the process.

With proper unit testing, we would not have had the trust and guts to make this radical change. We would just let it slide. And we would just let it slide over and over again. Until we would not be able to guarantee the quality of our codebases anymore.

My advice? Stop whining about the effort and time it takes to start writing unit tests. Or even complain about it being boring. Even though unit testing might not seem to deliver on its promises immediately, it will in the long run. For sure. Don’t wait until your code becomes unmaintainable. Just like you can better stop smoking today than to wait for your package to be empty, or until the first of January of next year. There is no excuse to postpone. It is always better to start writing unit tests today. Actually? Stop reading now, start unit testing.