If you, are working in technology, like me, there’s a chance that you live under the impression that our field changes faster than you can keep up with. Once you have learned how to work with the latest version of a technology of your choice – not even having mastered it – it will have evolved into a newer version, or even has been out-performed by another newer technology. I still remember when I first started investigating frameworks such as ember.js and knockout.js just a couple of years ago. At one time, not so long ago, they were the flavor of the month, until angular.js took over. From that point on, the world of JavaScript changed again.

From a higher perspective

But if you look at it from a somewhat higher perspective, in my opinion, the world of technology actually doesn’t change that fast after all. Let me illustrate this with some examples. With the introduction of programming languages such as Smalltalk and C++ object orientation was going to make it and rule the world of programming. However, it took until Java appeared on stage in 1996, and later C# in 2002, before the majority of programmers really picked up the concepts of object orientation. In 2002, object orientation was already around for more or less 35 years. Hardly a fast change, is it?

And what about JavaScript? The language that everybody now tries so hard to adopt and master? With new frameworks coming out every month, if not every week? It originated in 1995. Yes, next year its 20th anniversary will be celebrated. And it took at least 15 years before JavaScript finally really caught on.

What does history tell us about agile?

So what does the history of our field tell us about software development methodologies? Let’s start with waterfall. Although the term waterfall wasn’t mentioned in it, we consider the white paper Managing The Development Of Large Software Systems by Winston Royce to be the root of all evil in this case. Royce wrote his famous white paper in 1970. And although we left the waterfall heydays behind us, the model has been in use for over 50 years. And still is.

Skipping a generation of more iterative programming methodologies from the eighties, what does history tell us about agile? There are a lot of organizations where agile, extreme programming and Scrum are considered to be revolutionary or even disruptive. Still in 2014. The truth however is that agile is not exactly brand new either. Most of the agile approaches that we are so familiar with now first appeared n the second half of the nineties of the last century. Scrum as we know it, was first named Scrum in 1995, but the approach had already been described in 1986. Which means its ideas are almost 30 years old. Not really brand new either.

Presented with the facts that our ways of working change only slowly and that new ways will continue to be discovered, why is it so many people act as if the current state of agile is the final solution for all our problems. Scrum will solve all project managements issues, JavaScript will take over the world of programming, and with micro-services architectures we will finally be able to deliver on all of the promises component based development and service orientation made us. Following this point of view, organizations are setting up for the current state of agile, and forget to look beyond the ideas of the current generation of approaches. They will spend lots of effort to institutionalize Scrum, or maybe the enterprise editions of agile featured in SAFe or Agility Path, and stop to look further. As long as we do Scrum in all our projects, we’ll be fine.

Small evolutions

You probably will be fine indeed for quite a while. But that’s not what the historical view on our field should teach us. Rather it is what Jack Sparrow in Pirated of the Caribbean teaches us: It’s not so much the destination, but the journey. No approach, technology or framework will ever be the one to rule them all, not even angular.js. There is no disruptive revolution. There is only a continuous chain of small evolutionary steps building on top of previous ideas and foundations.

Having been in agile projects for over fifteen years, I see quite a lot of these interesting steps on my path. Let me try to explain a few of them:

- Sprints. The basic procedure of sprints in Scrum tells us that we are creating a potentially shippable product increment every sprint. I for one find it very hard to define an amount of work that exactly fits the next sprint and moreover adds to a new fantastic product in two or four weeks.

- Estimation. Let’s not forget to estimate the effort required to build this chosen amount of work (preferably in hours). Did you ever manage to do this right? To not underestimate or overestimate the amount of time needed? I’ve witnessed many teams being very disappointed not being able to deliver what they had estimated two or four weeks ago.

- Tasks. To be able to estimate, teams split up their backlog items into tasks. Usually this procedure takes a lot of debating and results in tasks such as “Design the web page”, “Build the logic” and “Test the web page.”

- Task boards. Most Scrum or agile projects monitor progress on a typical task board in three columns: To-Do, In Progress and Done. In my experience such a task board doesn’t really show actual progress. Ok, there’s a dozen of tasks in the In Progress column. What does that tell you?

So, do these little steps mean Scrum doesn’t work? They don’t. Scrum and Scrum-like approaches do work for a lot of organizations, projects and teams. However, these little steps should tell you not to stop at standardizing and institutionalizing agile. They should tell you that after twenty years, there’s more than meets the eye to agile projects. Time to move on again.

Flow

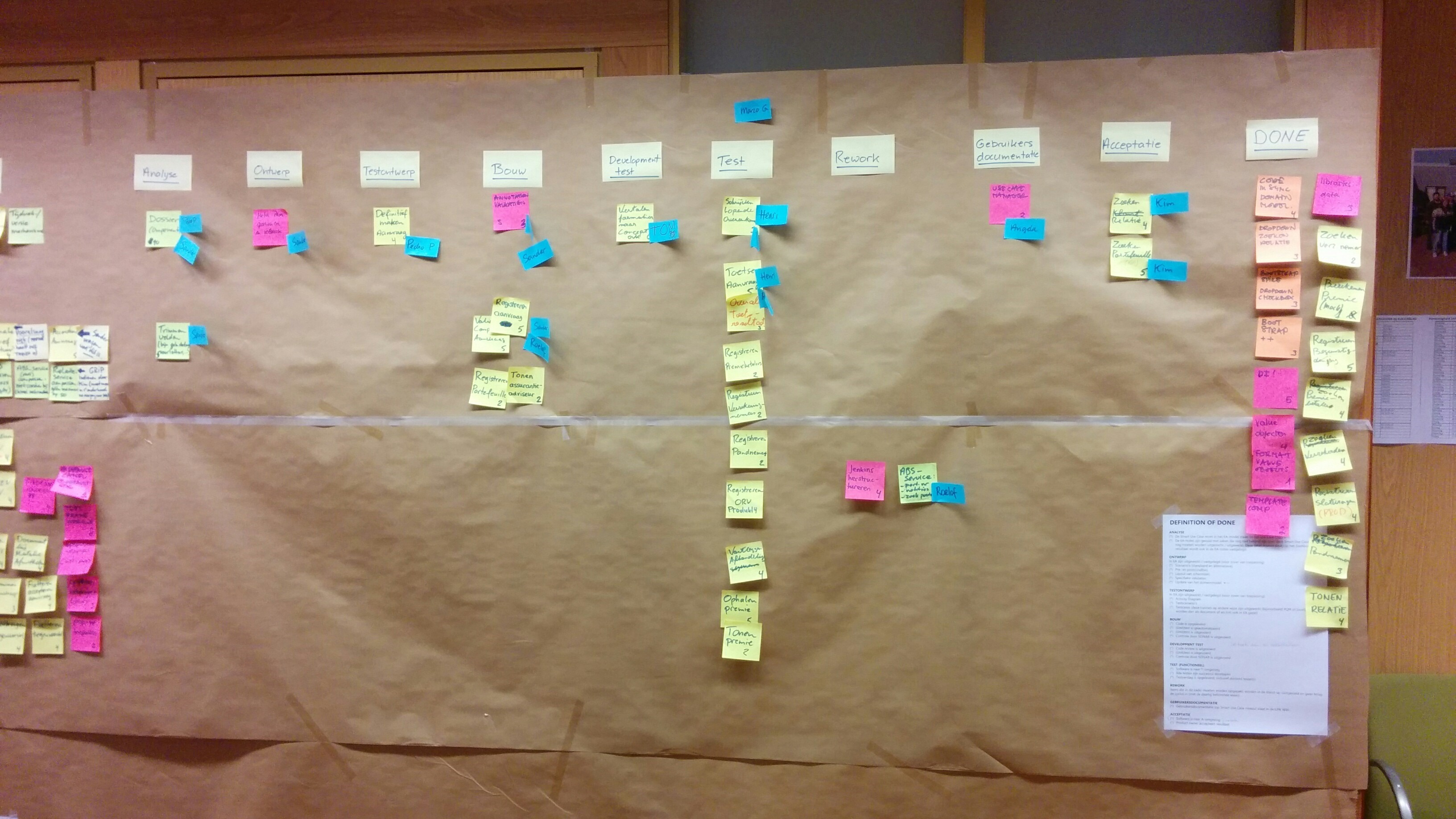

What if you would stop working in sprints? No two or four weeks mini-projects anymore to deliver a fully working piece of software. What if you would just pick the next backlog item from the product backlog as soon as there’s time available to start working on it. What if you would project the different activities on your backlog items in columns on your dashboard, and track the progress of the items by following their flow through these activities, instead of just saying they’re in progress? Dashboards such as the one below – taken from my current project – will give you such a projection.

There’s a lot of benefits in using this approach – and yes it does resemble Kanban:

- No tasks. First of all there’s no need anymore to break backlog items down into tasks. Usually the tasks you defined before will become activities in columns on the dashboard. Not having to break down you backlog items saves time and effort.

- No estimates. Not having to define the exact amount of work that can be done in a sprint means not having to estimate that work either. Estimates that are often incorrect anyway.

- Clarity. Your definition of done becomes more clear. You can attach conditions to pass on every column on the dashboard.

- Bottlenecks. At all time you will be able to spot the bottlenecks in the flow. It will simply be the column with the most post-its on it. Your flow is always as strong as its weakest link. Just look at the real-life example above. There’s a column named Test that has much more post-its to it than the other columns.

- Act. You will be able to act instantly upon the bottlenecks, and by doing so, optimize your team’s performance immediately.

- Deliver? So what happened to Scrum’s famous potentially shippable product increments? You can still deliver those after having implemented a number of backlog items. But, it doesn’t necessarily happen at the end of sprints only. It happens when the items are done, which can be at any given moment. Or you could even crank it some steps up, by delivering whenever a single backlog item is finished. It’s up to you how to set up your deployment. At best it can be continuous, but that requires a good infrastructure and a well-organized deployment pipeline.

- No sprints. Taking individual backlog items from the backlog to work on means the whole concept of sprints will become irrelevant. Your flow becomes continuous. The only real value of sprints that’s left is having retrospectives (and demo’s) every two to four weeks. We still do that.

The end of Scrum?

An interesting question rounding up this little history lesson is whether flow-based approaches herald the end of agile and Scrum as we know it? They don’t. Not yet, that is. Just remember how long waterfall approaches have ruled the earth. They’ve been around for 50 years, and are still in use. Scrum and agile are much younger, they are “only” in their twenties and thirties, so they will be around for quite some time. Your Scrum Master training is not a waste of money yet.

But in my opinion teams, especially teams with a wealthy experience in agile, will slowly start taking the next steps in delivering software. With a pipeline set-up and a flow-based approach to delivering individual backlog items, I think the need for working in sprints, and even working in projects will slowly fade away and make place for newer experiences. Remember Jack Sparrow’s words. Don’t get stuck on some agile tropical island. It’s the journey that counts.

2 thoughts on “Jack Sparrow and the End of Scrum”

Excellent article. I have faced similar challenges and blogged about the “sprint overhead” as well. Any suggestions on how to estimate the project release using this approach? JIRA for exmample provides estimated end-date by dividing total backlog divided by sprint velocity which is useful with executive reporting (although I agree its at best a guesstimate). Would a kanban style flow approach provide similar feedback?

It will, but not on a sprint basis. It will provide you of times spent on how long it takes to deliver individual items, and you can do the math from the average delivery times.

Comments are closed.