In 2009 I hired a building contractor to build a house. Together with an architect and the contractor I worked out the features. We wanted a basement, we carefully picked the materials, the location of the windows, the placement of the rooms, the bathroom, the attic and everything the contractor needed to come up with a price and a delivery date. About a year-and-a-half later the house was completed.

Looking at this project from a mile high, it appears to be a regular construction project. The requirements were specified, the contractor came up with a price and a date, and about a year-and-a-half later the project was delivered. One might suggest that this model for construction projects is a fairly suitable model for software development projects as well. You specify the requirements, set the price and delivery date, and of you go. And many managers and project managers actually do suggest this model for software development projects, supported by the fact that we have been using this model since the seventies, most often referred to as waterfall or linear.

Unfortunately, the waterfall or linear model, where we identify with all the requirements and pour them in concrete before we start the actual construction, doesn’t really work that well. Many, many contractors fail to meet their budget or deadline, or only deliver a very small part of the agreed requirements. Recent publications on large government projects in the Netherlands show dramatic negative results and failing projects. Clients blame contractors, and contractors in their turn blame clients for demanding the projects to be executed following this linear model. Many projects end in court and our beloved software development discipline has a negative public image.

So where does it all go wrong? Let me try and explain.

Software development is a very young discipline

When we try to model our software development projects to a metaphor coming from civil engineering we bypass the notion that civil engineering has been around for thousands of years. There is a world of experience and knowledge in construction from the Babylonians, the Greek, the Egyptians, the Middle Ages, Renaissance and industrial revolutions. Two thousand years ago the Romans already used concrete. All this experience contributes to how construction projects are executed today.

Roman concrete

Software development on the other hand is a very young discipline. Where mathematics and concrete have been around for a very long time, programming languages are only about sixty years old. Hence, applying a project model from a discipline from a thousands years old discipline might not fit very well. We just don’t have this experience. Yet.

Construction projects also fail

Nevertheless, even with these thousands of years of experience and technology development, construction projects using this one-pass model also still fail. Right after my new house was delivered by the contractor, we started noticing a terrible smell from the toilets. After two weeks the situation got worse. We couldn’t even flush the toilet anymore. The system was totally constipated. To cut a long story short, the contractor had totally forgotten to connect the house to the city’s central sewerage. Repairing this “bug” meant that my just finished garden was ruined.

So the single-pass model doesn’t really fit construction either. And building a single house is not that big a project. When you investigate much larger construction projects, projects that have actually implemented the agreed requirements on-time and on-budget are exceptions, not the rule. So if construction projects don’t even work on a linear model, how could software development projects?

In software development requirements can change

And there is more. When I had my house built, I needed to take a lot of decisions up front. Although I didn’t have to decide about how high on the wall the sockets were going to be placed, it isn’t hard to figure out that adding a basement after a house is fully completed is a lot harder than installing it before the floors are added. And the same goes for the sewerage. You could well say that most of the architecture and design needs to be done up-front. Software development however, is very, very different. Software can always change. Even late in a project we can change our requirements, the user interface, and even the architecture. Therefore, we do not need this big up-front design.

The fact that (too) many projects still rely on this big up-front design, is because we are applying the wrong model to our projects. Applying a big up-front design in software development projects has a negative effect on the outcome of these projects, because it disallows change. And change is beneficial. Being able to change during a project, even late in the project, simply improves quality, and improves the ability to maximize the benefits of the software we build for our clients.

The fact that we can change our requirements, design and even our architecture make software development projects very different other construction projects. Software is fluid, non-linear, and we should benefit from this.

Projects are not the right metaphor

And in my opinion, that’s not all. As said, after we worked out the features of my new house my contractor came up with a price and a delivery date. So we fixed the features, the price and the delivery date. Essentially the same three factors that are used to monitor the success of software development projects. Often I ask project managers to describe when they consider their projects to be successful. Continuously I get the response that if all the features are delivered on-time and on-budget the project is a success. But is it?

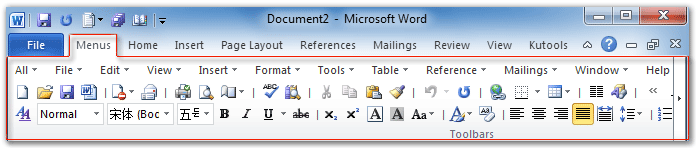

Please consider Microsoft Word. A product with thousands of features of which most people only use a very limited number of. Would it have been a successful product even if it only delivered this limited set of features? For a fraction of the budget it now took to build? My guess is it would. I traded in Microsoft Word for a simple, straightforward text editor long ago.

How many feature do you need in a text editor?

What if, instead of using the project model decides to build our software feature by feature? And if we would only build the minimum version of those features that does just enough. We could continuously ask the client how he of she wants to spend the next bit of time and money. Should we build a more fancy version of the current feature, or the minimum version of the next feature on the list? Every product build like this would have the minimum set of features, built for a minimal budget in a minimal amount of time. Delivered earlier than it would have been using a project model – linear or agile for that matter. Delivered cheaper that using a project model. And with only those features we really need. Built like this, Microsoft Word would have been a lean and mean editor, without all the abundant features it now has.

So I rest my case. In my opinion software should not be built using a project model. Never. Software should rather be implemented feature by feature, delivering a minimal viable product. And in case you’re wondering, my house was neither delivered on-time nor on-budget. So please stop doing projects.

One thought on “Why the project metaphor doesn’t fit software development”

I like the article, although the MS Word example is not completely correct. You might find the features abundant, but with every 20.000 users of Word, 100% of the functionality is used. You might just use 5% of the functionality but other people are using different 5% of the functionality. Word is build for 100s of millions of users and your house is build for 1 single family. Easier to come up with a feature set to agree up on up front 🙂

Although you see MS changing the model now. Building the modern touch office apps they release more often and respond to feedback for the following version and adjust accordingly. Although the basic architecture of the app was build up front.

Comments are closed.